iuniti fórlenguadges óv sáins

Gêneros discursivos: resenha de livro, coluna de opinião e conferência.

Tema: a língua inglesa e a difusão de conhecimento.

Os objetivos desta unidade são:

- familiarizar-se com os gêneros discursivos resenha de livro, coluna de opinião e conferência.

- refletir sobre a língua inglesa como um meio de adquirir conhecimento.

taimi tchu finqui

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

1.

II.

III.

d.

2.

b.

3.

A

B

Eyes on grammar – EXAMPLE 1

C

TANGERMANN, V. The 10 Most Significant Scientific Discoveries Of the Year (So Far). Futurism, 18 agosto 2017. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/rTShaD. Acesso em: 1º maio 2022.

4.

How did English become the language of science?

abre colchetereticênciasfecha colchete

Today though, if a scientist is going to coin a new term, it’s most likely in English. And if they are going to publish a new discovery, it is most definitely in English.

Look no further than the Nobel prize awarded for physiology and medicine to Norwegian couple May-Britt and Edvard Moser. Their research was written and published in English.

PORZUCKI, N. How did English become the language of science? The World, 6 outubro 2014. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/IiPE49. Acesso em: 30 abril 2022.

c.

rídin

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

tesqui uon

bifór rídin

2.

MONTGOMERY, S. L. Does Science Need a Global Language? Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

b.

ríd tchu lârn

Eyes on grammar –

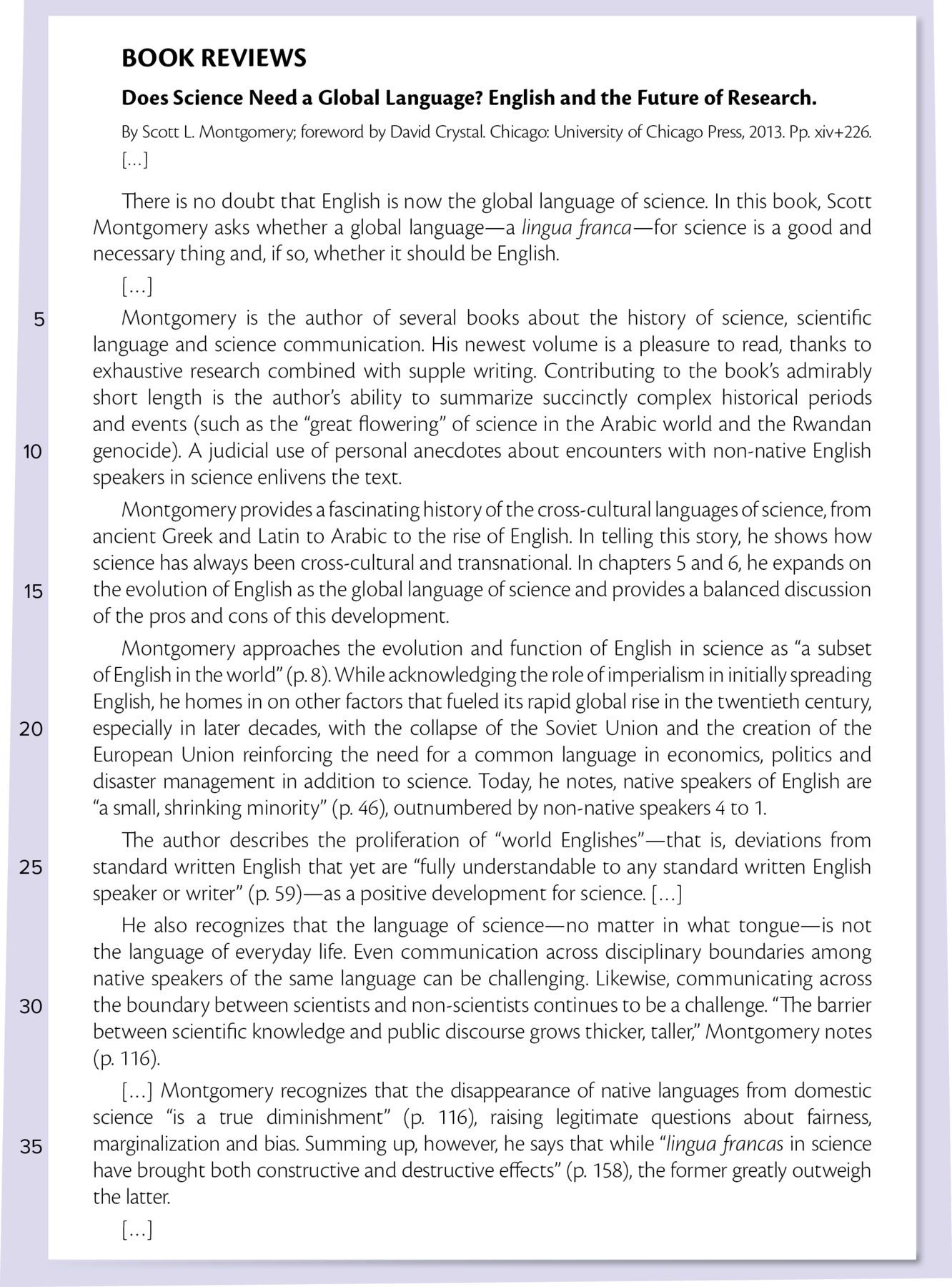

BILLINGS, L. Does Science Need a Global Language? English and the Future of Research. By Scott L. Montgomery (review). Technology and Culture, volume 56, número 1, página 261-263, janeiro 2015.

constrãquitchion minins

-

-

- lingua franca.

- .

-

-

- página

-

- .

- páginapágina

- lingua francas;

-

Versão adaptada acessível

Atividade 3, item c.

In the fragment “[…] while ‘lingua francas in science have brought both constructive and destructive effects’ (p. 158), the former greatly outweigh the latter” (p. 77), what do the words "the former" and "the latter" refer to, respectively?

- lingua francas; destructive effects

- constructive effects; destructive effects

- destructive effects; constructive effects

tésqui tchu

bifór rídin

- ríd tchu lârn

-

- ríd tchu lârn

ríd tchu lârn

Eyes on grammar – EXAMPLES 1, 2 AND 3

By Ben Panko

English Is the Language of Science. That Isn’t Always a Good Thing

How a bias toward Englishlanguage science can result in preventable crises, duplicated efforts and lost knowledge

Thirteen years ago, a deadly strain of avian flu known as H5N1 was tearing through Asia’s bird populations. In January 2004, Chinese scientists reported that pigs too had become infected with the virus—an alarming development, since pigs are susceptible to human viruses and could potentially act as a “mixing vessel” that would allow the virus to jump to humans. “Urgent attention should be paid to the pandemic preparedness of these two subtypes of influenza,” the scientists wrote in their study.

Yet at the time, little attention was paid outside of China—because the study was published only in Chinese, in a small Chinese journal of veterinary medicine.

It wasn’t until August of that year that the World Health Organization and the United Nations learned of the study’s results and rushed to have it translated. Those scientists and policy makers ran headlong into one of science’s biggest unsolved dilemmas: language.

“Native English speakers tend to assume that all important information is in English,” says Tatsuya Amano, a zoology researcher at the University of Cambridge and lead author on this study. Amano, a native of Japan who has lived in Cambridge for five years, has encountered this bias in his own work as a zoologist; publishing in English was essential for him to further his career, he says. At the same time, he has seen studies that have been overlooked by global reviews, presumably because they were only published in Japanese.

Yet particularly when it comes to work about biodiversity and conservation, Amano says, much of the most important data is collected and published by researchers in the countries where exotic or endangered species live—not just the United States or England. This can lead to oversights of important statistics or critical breakthroughs by international organizations, or even scientists unnecessarily duplicating research that has already been done. Speaking for himself and his collaborators, he says: “We think ignoring non-English papers can cause biases in your understanding.”

Amano thinks that journals and scientific academies working to include international voices is one of the best solutions to this language gap. He suggests that all major efforts to compile reviews of research include speakers of a variety of languages, so that important work isn’t overlooked. He also suggests that journals and authors should be pushed to translate summaries of their work into several languages so that it’s more easily found by people worldwide. Amano and his collaborators translated a summary of their work into Spanish, Chinese, Portuguese, French and Japanese.

PANKO, B. English is the language of science. That isn't always a good thing. Smithsonian Magazine, Washington, D.C., 2 janeiro 2017.

constrãquitchion minins

To demonstrate that research that is not published in espaço para resposta (Chinese - English) is often ignored.

f.

-

- báias

-

Versão adaptada acessível

Atividade 2, item b.

In the sentence “How a bias toward English-language science can result in preventable crises, duplicated efforts and lost knowledge”, which word can best replace "bias"?

- dislike

- fairness

- favoritism

- justice

-

- .

- .

- .

Versão adaptada acessível

Atividade 2, item c.

In the extract “Amano thinks that journals and scientific academies working to include international voices is one of the best solutions to this language gap.”, the word "gap" means

- complication.

- disparity.

- sameness.

-

- índequis

-

-

- .

Versão adaptada acessível

Atividade 3, item c.

What is the function of the reporting verbs (as "wrote" and "says") in some fragments of the text?

- Expressing the writer’s thoughts.

- Reporting someone’s exact words.

- Indicating the use of figurative words.

-

- médicine

- eduqueichion

think a lítol mór

-

- No texto da tesqui uon , afirma-se que há uma grande barreira entre o conhecimento científico e o discurso público. Que argumento vocês podem acrescentar, além dos apresentados no texto, para defender essa ideia? Por quê?

- Qual é a opinião comum aos textos das tésks e ? Vocês concordam com ela? Por quê?

- Vocês acham que a importância do inglês é a mesma na disseminação de qualquer tipo de pesquisa (por exemplo, um estudo sobre uma língua específica ou sobre a história de um país)? Justifiquem.

- Como vocês acham que a comunidade científica brasileira lida com a publicação de artigos em inglês?

- Depois de ler textos sobre inglês como língua global, qual é a opinião de vocês sobre esse assunto? Quais argumentos usariam para defender seus posicionamentos? Por quê?

lissenin

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

bifór listenin

-

- líssen tchu lârn

- ínlíssen tchu lârn

- .

líssen tchu lârn

Talk – Parts um and dois

Title: Communicating Science: How, When and What (Sheril Kirshenbaum)

Date: January 12, 2016

Source: American Psychological Association

COMMUNICATING Science: How, When and What (Sheril Kirshenbaum). 2016. Vídeo (21 minutos 50 segundos). Publicado pelo canal American Psychological Association. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/QonuXd. Acesso em: 1º maio 2022.

Clique no play e acompanhe a reprodução do Áudio.

Clique no play e acompanhe a reprodução do Áudio.

constrãquitchion minins

-

-

- .

- .

- molécular baiólodji.

-

II.

-

- “

- “

- “

d.

think a lítol mór

-

- De acordo com o que vocês ouviram, como acham que a comunicação entre o mundo acadêmico e o público pode ser melhorada?

- A conferencista considera que as pessoas querem saber sobre pesquisas científicas. Vocês concordam? Por quê? A situação entre estudantes é parecida com a do público em geral?

- Como os diferentes meios de comunicação podem contribuir para divulgar a ciência entre as pessoas?

- Como vocês podem relacionar os textos lidos em rídin com a conferência que ouviram em líssen tchu lârn?

lenguagi in équitchon

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

- ênd

“Even communication across disciplinary boundaries among native speakers of the same language can be challenging. Likewise, communicating across the boundary between scientists and non-scientists continues to be a challenge.” (página 77)

b.

“Summing up, however, he says that while ‘lingua francas in science have brought both constructive and destructive effects’ the former greatly outweigh the latter.” (página 77)

- bicóspágina

- táime.

- rrison.

- cóntrést.

- .

2. tésqui tchu

“Yet at the time, little attention was paid outside of China—because the study was published only in Chinese, in a small Chinese journal of veterinary medicine.” (página 80)

“Yet particularly when it comes to work about biodiversity and conservation, Amano says, much of the most important data is collected and published by researchers in the countries where exotic or endangered species live—not just the United States or England.” (página 80)

- bãt

Versão adaptada acessível

Atividade 2.

In the fragments above, the word "yet" could be replaced by

- but

- when

- for instance

3. tíéf

Eyes on grammar – EXAMPLE 3

“According to our estimate, there are approximately 73,000 tree species on Earth, and more than 12 per cent of them haven’t been documented yet.”

LIANG, J.The Trees of Life. New Scientist, Londres, número3376, página 27, 5 março 2022.

“In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is not yet tracking BA.2 separately.”

WADMAN, M. New Omicron begins to take over, despite late start. Science, volume375, número6 580, página 480-481, 4 fevereiro 2022.

b.

- ênd

“It wasn’t until August of that year that the World Health Organization and the United Nations learned of the study’s results and rushed to have it translated.” (página 80)

In the previous excerpt, the first “that” indicates a year in the espaço para resposta (future/past), while the second “that” introduces a statement.

b.

“He suggests that all major efforts to compile reviews of research include speakers of a variety of languages, so that important work isn’t overlooked. He also suggests that journals and authors should be pushed to translate summaries of their work into several languages so that it’s more easily found by people worldwide.” (página 80)

Both uses of “so that” in the fragment express the same idea: the idea of espaço para resposta (um) (consequence/contrast).

The two instances of “that” following the verb “to suggest” espaço para resposta (dois) (explain/introduce) advice.

c.

“In January 2004, Chinese scientists reported that pigs too had become infected with the virus — an alarming development, since pigs are susceptible to human viruses and could potentially act as a “mixing vessel” that would allow the virus to jump to humans.” (página 80)

The first use of “that”, following the verb “to report” espaço para resposta (um) (explains/introduces) a statement, while in the second use, following “mixing vessel”, it could be replaced by espaço para resposta (dois) (“which”/“who”).

d.

“The author describes the proliferation of ‘world Englishes’ — that , deviations from standard written English that yet are ‘fully understandable to any standard written English speaker or writer’ (página 59)—as a positive development for science.” (página 77)

The use of “that is” in the previous excerpt indicates an espaço para resposta (explanation/introduction) of what was said before.

ispíquin

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

rit de rroudi

In pairs, you are going to produce a talk about English as the global language of science. Remember that you have already seen an example of a talk in Listening.

1.

For the oral production

What is the discursive genre? A talk.

What is the theme? English as the global language of science.

What is the objective? To give your opinion about the theme.

At whom is it aimed? Your classmates.

How and where is it going to be presented? In the classroom.

Who is going to participate? All students, organized into pairs.

túlbóks

- rídin

h.

Versão adaptada acessível

Atividade 1, item h.

Now you are ready to give the first version of your talk. Present it to another pair of students and ask for their feedback on what could be improved. You should rehearse your lines before presenting your talk. Remember that a talk must sound natural, so you cannot read a text. Face the audience, establishing contact with them, to try to make it more interactive. The way you behave can make all the difference.

istép béqui

2.

piti istopi

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

thinkirôver

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

-

- Consigo ler resenhas de livros e colunas de opinião?

I.

II.

III.

b. Consigo identificar argumentos em artigos de opinião?

I.

II.

III.

c. Aprendi algo novo sobre a língua da ciência?

I.

II.

III.

d. Posso compreender e preparar conferências?

I.

II.

III.

e. Participei ativamente durante as aulas, cooperando com o professor ou a professora e os ou as colegas?

I.

II.

III.

áison grémer

Leia os exemplos extraídos do texto desta unidade, bem como as palavras e as expressões destacadas. Preste atenção às observações que as seguem.

Versão adaptada acessível

Eyes on Grammar.

Leia os exemplos extraídos dos textos desta unidade. Preste atenção às palavras e expressões que serão explicadas pelas observações que as seguem.

egzâmpol uan

“Scientists Discovered an Alien Planet That’s the Best Candidate for Life As We Know It”

(página75)

“The author describes the proliferation of ‘world Englishes’ — that is, deviations from standard written English that yet are ‘fully understandable to any standard written English speaker or writer’ (p. 59)—as a positive development for science.”

(página77)

“It wasn’t until August of that year that the World Health Organization and the United Nations learned of the study’s results and rushed to have it translated.”

80)

“He suggests that all major efforts to compile reviews of research include speakers of a variety of languages, so that important work isn’t overlooked.”

(página80)

|

Demonstrative / Demonstrativo |

|---|

|

that year |

|

Verb + “that-clause” / Verbo + “that-clause” |

|

suggests that |

|

Conjunction (Purpose) / Conjunção (Propósito) |

|

so that |

|

Connector (Explanation) / Conector (Explicação) |

|

that is |

|

Relative Pronoun / Pronome Relativo |

|

that (which) |

egzâmpol tchu

“Even communication across disciplinary boundaries among native speakers of the same language can be challenging. Likewise, communicating across the boundary between scientists and non-scientists continues to be a challenge.

Summing up, however, he says that while ‘lingua francas in science have brought both constructive and destructive effects’ (página 158), the former greatly outweigh the latter.”

(página 77)

“Yet at the time, little attention was paid outside of China — because the study was published only in Chinese, in a small Chinese journal of veterinary medicine.”

(página 80)

|

Reason / Causa |

because, for, since |

|---|---|

|

Similarity / Semelhança |

likewise |

|

Summary / Resumo |

in sum; summing up |

• Conectores podem ter diferentes significados de acordo com o contexto.

“The author describes the proliferation of ‘world Englishes’ — that is, deviations from standard written English that yet are ‘fully understandable to any standard written English speaker or writer’ (página 59)—as a positive development for science.”

(página 77)

“Yet at the time, little attention was paid outside of China — because the study was published only in Chinese, in a small Chinese journal of veterinary medicine.”

(página 80)

|

Conjunction (Contrast) / Conjunção (Contraste) |

|---|

|

“The author describes the proliferation of ‘world Englishes’ — that is, deviations from standard written English that yet are “fully understandable […].” (p. 77) |

|

Adverb (Time) / Advérbio (Tempo) |

|

“According to our estimate, there are approximately 73,000 tree species on Earth, and more than 12 per cent of them haven’t been documented yet.” (p. 86) |

• iéti é uma conjunção que expressa contraste, como bãt, rrauévâr . Pode também ser um advérbio, referindo-se a um tempo que começa no passado e continua até o presente. Usado principalmente nas fórmas negativa e interrogativa.