iuniti eitchi

AMÉRICA do Sul. Rio de Janeiro: í bê gê É, 2018. 1 mapa, color.

Gêneros discursivos: postagem em blogue e debate oral.

Tema: descolonização e língua.

Os objetivos desta unidade são:

- familiarizar-se com os gêneros discursivos postagem em blogue e debate oral;

- refletir sobre os processos de colonização e de descolonização e suas relações com as línguas.

taimi tchu finqui

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

II.

Did you know?

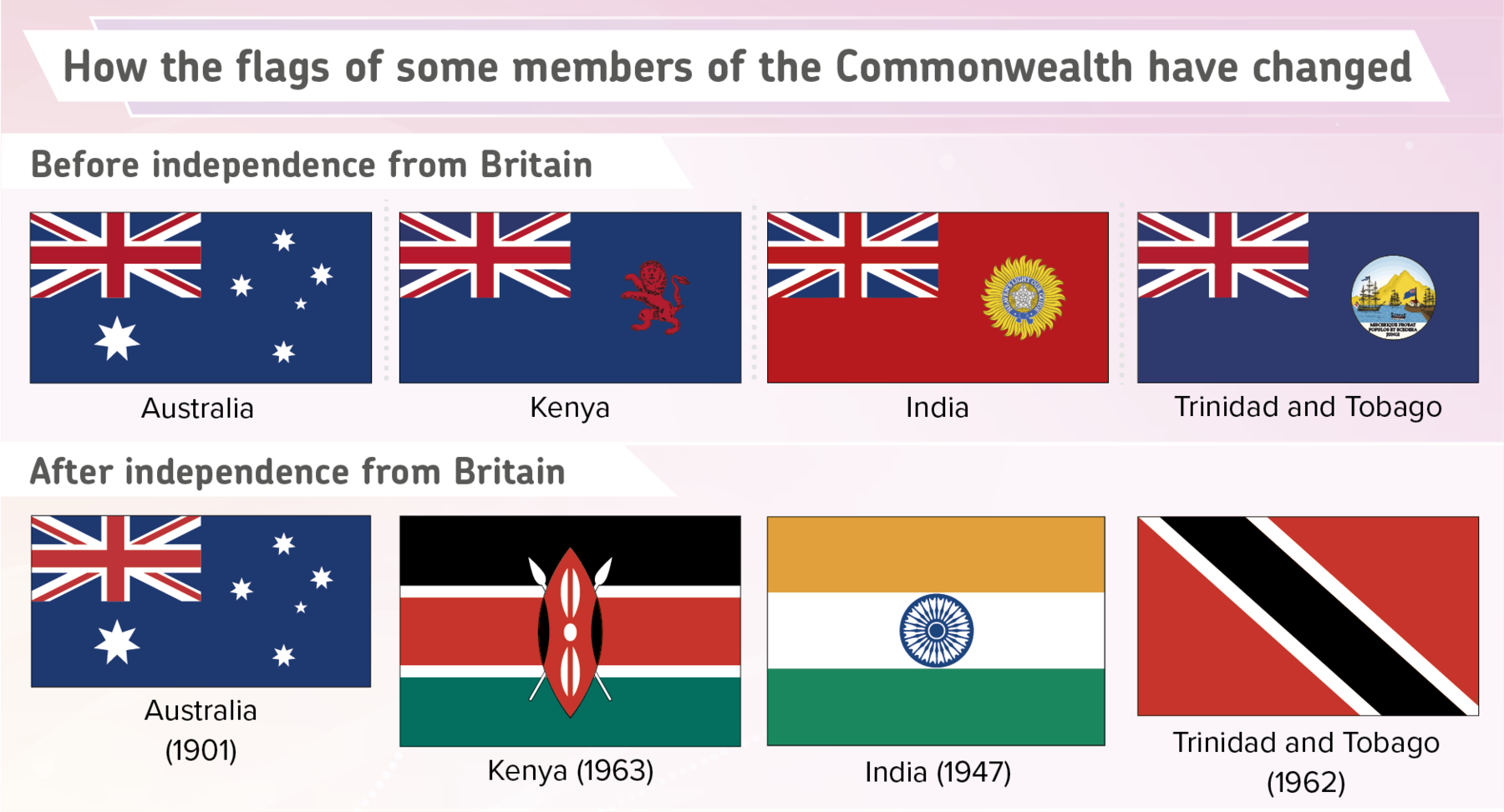

• A Comunidade das Nações (comon uélf ófi nêichons) é um grupo de 53 países, quase todos antigas colônias do Império Britânico.

Did you know?

• Colonização é a conquista e o comando de um lugar e seus povos por um poder externo. A colonização de muitas partes do mundo por europeus criou impérios que dominaram a maior parte do mundo. Esse sistema de dominação, chamado colonialismo, envolveu exploração econômica, escravidão e imposição de línguas e culturas europeias. O termo descolonização descreve como territórios dominados e seus povos conquistaram sua independência. O Império Britânico foi o maior império da história, controlando quase um quarto da população mundial no século vinte. Entretanto, na segunda metade do século vinte, movimentos pela independência forçaram os britânicos a deixar a Índia (1947) e a maior parte da Ásia, da África e do Caribe (nas décadas de 1950 e 1980). Com a descolonização, muitas antigas colônias promoveram culturas e línguas locais. Porém, um legado do Império Britânico é a difusão do inglês ao redor do mundo.

4.

“Language was always the companion of the empire.”

Antonio de Nebrija (1441-1522)

b.

Did you know?

• O espanhol Antonio de nebrirra (1441-1522) foi o autor da primeira gramática da língua castelhana (1492).

rídin

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

tesqui uon

bifór rídin

- ríd tchu lârn

-

- .

- .

- .

-

- ríd tchu lârn

-

- iispénish

-

Did you know?

• O número de línguas faladas na Nigéria é 526. Destas, 519 estão vivas e sete estão extintas. Das línguas vivas, 509 são originárias do continente africano. Além disso, 19 são institucionais, 78 estão em desenvolvimento, 348 são vigorosas, 30 estão com problemas e 44 estão morrendo.

EBERHARD, D. M.; SIMONS, G. F.; FENNIG, C. D. (edição). Ethnologue: Languages of the World. vigésima primeira edição Dallas, Texas: SIL International, 2022.

ríd tchu lârn

Eyes on grammar – EXAMPLES 1 and 2

![Reprodução de página da internet. No canto superior esquerdo, logotipo em verde arredondado e círculo em marrom. No menu superior se lê: PARADIGM INITIATIVE. Menu: Home, About, Blog, Contact Us. À direita, ícone de lupa ao lado de três linhas finas na horizontal. No banner da página se lê: Monthly Archives July 2016. No título se lê: Should Indigenous Languages be used for teaching in Nigeria? Em destaque, ao lado do título, se lê: JULY 24 e abaixo dele: By Umar Abdullahi. Abaixo, se lê o texto: Over the weekend, I was replaying a conversation I had on Friday in my head. The topic was “The use of native language as a medium of instruction in Nigeria.” I got to hear opinions both for and against the practice. On one side are those who feel teaching children in their native language will help them grasp it more quickly and increase the level of innovation. On the other are those who believe [that], by using English, (line five) children are being prepared for a leading role not just in their communities but also in the outside world. I have thought about these arguments and can see the merit in both of them. If you teach a child in his/her native language, understanding is bound to be quicker. Russians learn in Russian. [The] French [people] learn in French. Arabs learn in Arabic. Why should a Nigerian be any different? Unfortunately, the demonym “Nigerian” points to the crux of the matter. There is no universal Nigerian language. Rather, we (line ten) acknowledge over 350 spoken indigenous languages across the country. Which would you have teachers use in schools? We would need to train an army of translators to make sense of documents typed in one community that need to be sent to another. Furthermore, there is no point [in] trying to come up with textbooks in indigenous languages if there are (line fifteen) no words in those languages for some concepts. To use the example that was given in the conversation I referenced earlier, what is the word for “microchip” in your language? An answer doesn’t easily spring to mind. This should be taken as a challenge to our students in departments of Technology across the nation. They could start a project in collaboration with those in the Department of Languages to translate some technological concepts and terms into our local languages. You are not likely to ever build a microchip if you keep thinking of it as something from a foreign country. (line twenty) In a country like Nigeria, which is often divided across ethnoreligious lines, a case could be made that the use of English as a national language actually helps the cause of national unity and prepares everyone for being able to communicate should they find themselves outside their community. What would happen if I went to address the National Assembly in my mother tongue, you rose to oppose me in yours, the Speaker tries to mediate in his while the Clerk tries to record what is being said in a fourth? (line twenty-five)For better or for worse, I think the use of English as a medium of instruction in Nigerian schools is here to stay. However, I believe there is room for communities to organise specialised training programs, seminars and workshops for their members in the local language of that community. Such a bold step may be necessary if we are to successfully address the innovation gap between us and more technologically advanced parts of the world. For so long, we have been speaking about “catching up”. Such a thing won’t happen until we start looking (line thirty)for home grown solutions to problems. Perhaps the first step towards achieving that would be for us to receive at least some of our learning in the same languages we speak at home. I don’t speak English in casual conversation unless the other person I’m addressing doesn’t speak Hausa. Neither do I think in English. Do you? Umar Amir Abdullahi works at Paradigm Initiative Nigeria as Program Assistant, DakataLIFE](../resources/images/im_156_175_bw9_u08_f2_g24_group_546081_1.png)

ABDULLAHI, U. Should Indigenous Languages be used for teaching in Nigeria? Paradigm Initiative, 24 julho 2016. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/mqyBTI. Acesso em: 2 maio 2022.

Constructing meanings

- tíéf

3.

- dídiunôu?

e.

tésqui tchu

bifór rídin

1.

2.

I.

Why has it become so acceptable to know English but not know Urdu?

MOHASIN, A. Why has it become so acceptable to know English but not know Urdu? The Express Tribune, Paquistão, 20 fevereiro 2016.

II.

No English Please, We’re Pakistani

PILLALAMARRI, A. No English Please, We’re Pakistani. The Diplomat, Washington, D.C., 17 julho2015.

III.

National language 251.

(1) The National language of Pakistan is Urdu, and arrangements shall be made for its being used for official and other purposes within fifteen years from the commencing day.

(2) Subject to clause (1), the English language may be used for official purposes until arrangements are made for its replacement by Urdu.

(3) Without prejudice to the status of the National language, a Provincial Assembly may by law prescribe measures for the teaching, promotion and use of a provincial language in addition to the National language.

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PAKISTAN. The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (updated version of the 1973 edition). Islamabade, 2012.

3. ríd tchu lârn

ríd tchu lârn

Eyes on grammar – EXAMPLE 2

Urdu vs English: Are we ashamed of our language?

By Amna Khalid Published: June 21, 2011

Most Pakistanis have been brought up speaking our national language Urdu and English. Instead of conversing in Urdu, many of us lapse into English during everyday convers ation. Even people who do not speak English very well try their best to sneak in a sentence or two, considering it pertinent for their acceptance in the “cooler” crowd.

I wonder where the trend started, but unknowingly, unconsciously, [one way] or the other we all get sucked into the trap. It was not until a few years ago while on a college trip to Turkey that I realized the misgivings of our innocent jabber.

A group of students of the LUMS Cultural Society trip went to Istanbul, Turkey, to mark the 100th Anniversary of the famous Sufi poet Rumi. One day, we were exploring the city when we stopped at a café for lunch. The waiter took our orders and continued to hover around our table during the meal. We barely noticed him until he came with the bill and asked us:

“Where are you from?”

“Pakistan.”

The waiter looked surprised and then asked whether we had been brought up in England. We answered in the negative, telling him how Pakistan was where we all had grown up and spent our lives. The waiter genuinely looked perplexed now. Finally, he blurted out:

“Then why don’t you speak in the Pakistani language?”

The waiter went on to explain how Turkey, particularly Istanbul was a hot tourist location, luring millions of people of different nationalities from across the globe. However, when the Dutch would come visit, they would speak Dutch. When the French would come, they would speak French. When the Chinese would come visit, they would speak Chinese. Similarly, everyone in Turkey spoke Turkish.

He claimed he was very proud of his language and culture and failed to understand how someone would not speak the language of their country and choose instead a foreign tongue.

There were around ten of us there, and we were all at a loss of an answer. We had never thought of it that way. It was just something that you took up because of society. Even when people speak in Urdu, they tend to include a lot of English words in their sentences. Why is that? Is it because we are not proud of our national language? I am sure all of us are aware of how beautiful Urdu is, the poetry, grace and rhythm of our language is exceptional.

One excuse that springs to mind is the concept of “westernisation” due to the increased pace of globalization in today’s world. Globalization is a factor, and yet the Japanese still speak Japanese, the Thai still speak Thai, the Greeks still speak Greek. China, a powerhouse on the global economic front, despite its many factories and western products production, still speaks Chinese. In fact, when the Chinese Olympics were held in 2008, the Chinese government actually had to ask its Chinese public to learn a few basic English words to help welcome the world.

I respect how these countries value their sense of identity, culture and language. I was deeply ashamed of what image I was unknowingly portraying of my country. I am very proud of Pakistan and Urdu, as I am sure we all are. No matter the problems, it is still our identity. I understand the irony of this article, since it is written in English. However, it is one way to reach those people who may unconsciously be making the same mistake as I was.

When living in the UK or travelling abroad, I make sure I use Urdu to converse with fellow Pakistanis. At home, I am also trying, though it is admittedly difficult since apparently there is a weird and honestly “sad” association of how “cool”, well brought-up and educated a person is with the amount of English he or she speaks. I write this article because it is high time we break such ignorant patterns in our society. Urdu is a beautiful and graceful language and we owe our country the respect it deserves by speaking and portraying our true roots.

Kiya khayal hai?

KHALID, A. Urdu vs English: Are we ashamed of our language? The Express Tribune, 21 junho2011. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/M9nw93. Acesso em: 2 maio 2022.

constrãquitchion minins

2. Read the sentence and do the following.

“One excuse that springs to mind is the concept of ‘westernisation’ due to the increased pace of globalization in today’s world.”

a.

- Choose the best option.

-

- tíéf

- .

think a lítol mór

-

- Com qual dos seguintes pontos de vista, mencionados na tesqui uon , vocês concordam? Por quê?

- Nigerianos deveriam aprender em inglês.

- Nigerianos deveriam aprender em suas línguas nativas.

- Nigerianos deveriam aprender em inglês e também em suas línguas nativas.

- Vocês acham que as discussões das tésks e seriam válidas no Brasil? Por quê?

- Pessoas que falam outras línguas no Brasil, como línguas de povos originários, deveriam ter o direito de usá-las na escola? Justifiquem.

- Vocês concordam que, no geral, postagens de blogue possibilitam que as pessoas expressem suas opiniões sobre assuntos importantes? Expliquem.

- Se vocês fossem escrever postagens de blogue sobre assuntos relacionados ao Brasil, sobre o que escreveriam? Por quê?

- Com qual dos seguintes pontos de vista, mencionados na tesqui uon , vocês concordam? Por quê?

lissenin

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

bifór listenin

-

- .

- .

- .

- .

2.

OFFICIAL LANGUAGE POLICY OF THE UNION

Hindi in Devanagari script is the official language of the Union. In addition to Hindi language, English language may also be used for official purposes.

It has been the policy of the Government of India that progressive use of Hindi in the official work may be ensured through persuasion, incentive and goodwill.

NORTH EAST REGIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION. Official Language Implementation Committee.Official Language Policy of the Union. Shillong: NERIE/OLIC, 2007. página 1.

c.

Did you know?

• (inglês indiano) é o termo usado para a variedade do inglês falado na Índia. O sotaque é influenciado por línguas locais, como o híndi. Algumas pronúncias são diferentes; por exemplo, muitos falantes pronunciam as letras w e v de fórma similar. Também há algumas palavras diferentes; por exemplo, a palavra “métrou”, que em inglês britânico significa “metrô”, significa “região metropolitana” em inglês indiano.

Listen to learn

Eyes on grammar – EXAMPLE 2

Oral debate – Parts um, dois and três

Title: Language: Bridge or Divide?

Date: May 14, 2017

Source: We the People, NDTV

WE the People. Nova Delhi: NDTV, 14 maio 2017.

Clique no play e acompanhe a reprodução do Áudio.

Clique no play e acompanhe a reprodução do Áudio.

Clique no play e acompanhe a reprodução do Áudio.

constrãquitchion minins

- um

- um

-

- bíznes.

- líteratiur.

- .

- .

- .

- .

- .

- .

- .

-

- tíéfum

- dois

- três

Although a large part of the population speaks Hindi, espaço para resposta , whether it’s a small town or a big city.

c.

6. umdoistrês

Ashok Vajpeyi (A) Chetan Bhagat (C) the host (H)

f.

Think a little more

-

- Baseado nos argumentos apresentados, comentem sobre o assunto discutido no debate oral.

- O que há em comum entre esse debate oral e as postagens de blogue que vocês leram em rídin?

- Na opinião de vocês, por que é tão importante discutir a língua falada ou as línguas faladas em um país?

- Essa discussão é relevante no Brasil? Por quê?

- Quais ligações vocês podem estabelecer entre descolonização e discussões sobre as línguas faladas em países que já foram colônias?

lenguagi in équitchon

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

1. página

“Over the weekend, I was replaying a conversation I had on Friday in my head. The topic was ‘The use of native language as a medium of instruction in Nigeria.’ I got to hear opinions both for and against the practice.

On one side are those who feel teaching children in their native language will help them grasp it more quickly and increase the level of innovation. On the other are those who believe [that], by using English, children are being prepared for a leading role not just in their communities but also in the outside world.”

- fórênd

- “

- “

-

- .

- .

2. tíéf

“For better or for worse, I think the use of English as a medium of instruction in Nigerian schools is here to stay.”

c.

3.

“There is no universal Nigerian language. Rather, we acknowledge over 350 spoken indigenous languages across the country. Which would you have teachers use in schools?

Furthermore, there is no point [in] trying to come up with textbooks in indigenous languages if there are no words in those languages for some concepts. To use the example that was given in the conversation I referenced earlier, what is the word for ‘microchip’ in your language? An answer doesn’t easily spring to mind.”

c.

- following

“Should African writers write in English? Chinua Achebe thinks we should Ngũgĩ, on the other hand, believes that it is important to write in one’s mother tongue

AFROWRITE. English Language: Should African Writers Use Local Languages Instead? Afrowrite’s Weblog, 25 outubro 2009. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/AcCkYr. Acesso em: 2 maio 2022.

b.

“Language is a medium of communication that helps us expressing and conveying our thoughts, feelings, and emotions of two individuals. Moreover, Language depends on verbal or non-verbal codes.”

THE LANGUAGE DOCTORS. Language and Communication – A Detailed Guide. The Language Doctors, 30 mar. 2021. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/TSgIe8. Acesso em: 2 maio 2022.

c.

“In sum, I’m not saying that learning a language into adulthood is a fool’s errand. I’m a language learner. I love it and I hope to always be one.”

SCOTT, 15 março 2014. In: FERRISS, T. 12 Rules for Learning Foreign Languages in Record Time — The Only Post You’ll Ever Need. The Tim Ferriss Show, 21 março2014. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/nvmWmE. Acesso em: 2 maio 2022.

d.

“It reveals the internal struggle of, on the one hand, wanting to take pride in one’s heritage while on the other hand ‘not really believing it’

RUTGERS, D. Stories of Multilingualism. MEITS Blog, 6 dezembro 2017. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/TPK9dY. Acesso em: 2 maio 2022.

5. tesqui uon rídin

“For better or for worse, I think the use of English as a medium of instruction in Nigerian schools is here to stay. However, I believe there is room for communities to organise specialised training programs, seminars and workshops for their members in the local language of that community.” (página 161)

“Should African writers write in English? Chinua Achebe thinks we should Ngũgĩ, on the other hand, believes that it is important to write in one’s mother tongue

AFROWRITE. English Language: Should African Writers Use Local Languages Instead? Afrowrite’s Weblog, 25 outubro2009. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/AcCkYr. Acesso em: 2 maio 2022.

b.

“In my opinion it is the wisest article about why people should learn English I have ever read.”

BEATA, 18 janeiro 2017. In: KAUFMANN, S. Why English is Important. The Linguist, 21 abril2020. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/fPHryM. Acesso em: 2 maio 2022.

c.

“In Vygotsky’s view, speech is an extension of intelligence and thought, a way to interact with one’s environment beyond physical limitations

LOWE, H. The importance of language in cognitively challenging learning. NACE, 8 novembro 2021. Disponível em: https://oeds.link/JrCjMH. Acesso em: 2 maio 2022.

7. following conversation

ispíquin

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

rit de rroudi

You are going to participate in an oral debate about the use of Portuguese in original peoples’ communities, relating the discussions of the texts in this unit to your context. The debate will occur simultaneously in groups of five students. In each group, students will participate individually, advocating their personal position. Remember you have already seen an example of oral debate in Listening.

1.

For the oral production

What is the discursive genre? Oral debate.

What is the theme? The use of Portuguese in Brazilian original peoples’ communities.

What is the objective? To convincingly argue for or against the proposition.

At whom is it aimed? Your classmates.

How and where is it going to take place? In groups, in class.

Who is going to participate? All students, organized into groups of five.

túlbóks

1.

a.

b. lênguadj ís ór lênguadjes ár

c.

d. áison grémerquíu cárds

f.

Versão adaptada acessível

Atividade 1, item f.

Practice your arguments by speaking slowly and clearly and facing your audience.

istép béqui

2.

piti istopi

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

thinkirôver

Faça no caderno as questões de resposta escrita.

-

- Consigo ler postagens de blogue?

I.

II.

III.

b. Compreendo debates orais?

I.

II.

III.

c. Consigo falar sobre línguas nativas das antigas colônias britânicas?

I.

II.

III.

d. Aprendi algo novo sobre descolonização?

I.

II.

III.

e. Participei ativamente das aulas, cooperando com o ou a professor ou professora e os ou as colegas? Como?

I.

II.

III.

áison grémer

Leia os exemplos extraídos dos textos dessa unidade, bem como as palavras e expressões destacadas. Preste atenção às observações que as seguem.

Versão adaptada acessível

Eyes on Grammar.

Leia os exemplos extraídos dos textos desta unidade. Preste atenção às palavras e expressões que serão explicadas pelas observações que as seguem.

egzâmpol uan

“On one side are those who feel teaching children in their native language will help them grasp it more quickly and increase the level of innovation. On the other are those who believe [that], by using English, children are being prepared for a leading role not just in their communities but also in the outside world.

Furthermore, there is no point [in] trying to come up with textbooks in indigenous languages if there are no words in those languages for some concepts.

For better or for worse, I think the use of English as a medium of instruction in Nigerian schools is here to stay.”

(página161)

|

Addition / Adição |

Furthermore |

|---|---|

|

Opposition / Oposição |

On one side… On the other (side) |

|

Synthesis / Síntese |

For better or for worse |

• Conectores podem ter diferentes significados de acordo com o contexto.

egzâmpol tchu

I think the use of English as a medium of instruction in Nigerian schools is here to stay. However, I believe there is room for communities to organise specialised training programs, seminars and workshops for their members in the local language of that community.”

(página 161)

“I am sure all of us are aware of how beautiful Urdu is

(página 164)

“I think that, how you define it… What he’s saying is, it’s not used as much.”

(página167; Oral debate - Parts um, dois, and três)

|

Affirmative / Afirmativo |

Negative / Negativo |

|---|---|

|

I/We think (that) |

I/We don’t think (that) |